Hannah, my mother, who died last week after a long illness, loved fish and chips and she loved to travel. She loved France and tennis, cream teas, curries, chocolate and sherry. She loved to gossip and she loved to laugh. She loved to tell stories and she loved people – but most of all – she loved us.

Some people fizz with life – Hannah burned like a comet. She lit up everything. At any event she would home in on people and disarm them with her gregarious nature and very un-British and distinctly un-Southern manner. It didn’t matter if you were a Prime Minister – of whom she met several – or a casual acquaintance on the train, or an eight-year old in the back of her car. Everyone got the same treatment. The same jokes, stories and insights. She turned the morning school run into an impromptu classroom. My fellow passengers, captives on the good ship Hannah, were bombarded with questions and bits of information she’d heard on the radio – it was less a car journey, more a seminar.

She turned the dull monotony of life to light; Hannah lived in technicolour.

Born in a Staffordshire pit village a few years before the start of the war she was the sixth child of seven. Her father was a veteran of the so-called Great War – and in retrospect – damaged by it. Hannah aspired to a different life.

‘She was always too good for us!’ Her sisters used to say to me. But she never thought she was. It wasn’t so much airs and graces that she had, more drive, energy and ambition.

She passed the 11 plus and got a place at grammar school in the midst of war. Her father told her it would be impossible to go ‘because I can’t afford the bus fare’ so she said she’d walk.

“I’m not letting you walk either. It’s too far.”

And a tug of war ensued – which she won – she usually did.

From school she went to secretarial college and changed the way she spoke – because back then people who wanted to ‘get on’ had to sound like a plummy announcer on the BBC. And at the same time, she began to broaden her social circle.

By the early 1950s she was engaged in politics and campaigning for the local Tory candidate. Soon she was being pursued by a young Geoffrey Howe, who followed her all the way back to that tiny hill village and sat by the gate looking sorry for himself until my grandfather came out to tell him that she wasn’t interested – as Mum hid behind the curtains.

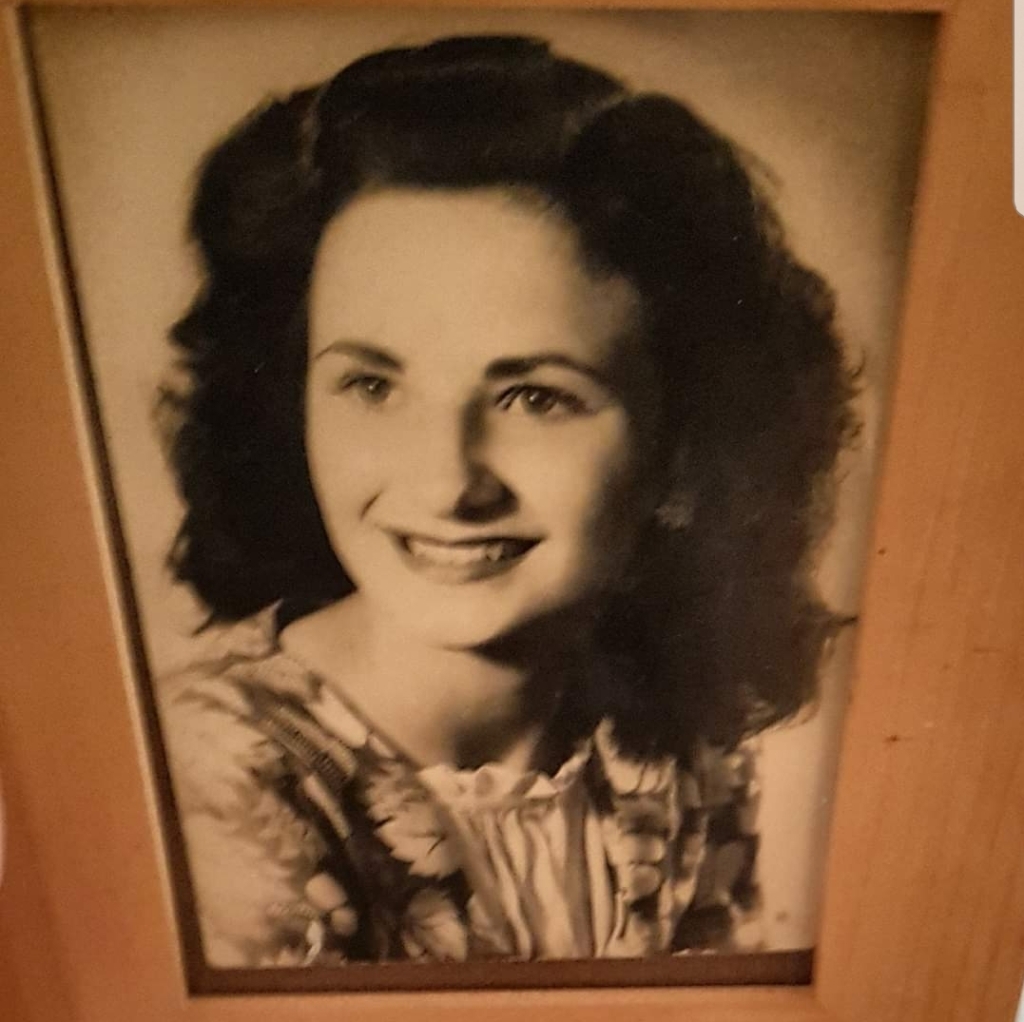

Photos show an impossibly glamorous woman – with a twinkle in her eye.

“She was like a movie star, your mother,” people used to say.

Eventually she moved to London and worked as a secretary for a Tory MP. On New Year’s Eve 1961, she met my father at a party. Mum loved parties – and was always – and I mean always – the last to leave

My parents were lucky to find each other. They fell in love and married. Three years later my sister was born and I came a few years after that.

And for most of my life I took what followed for granted. I thought it was normal for people to tell you they loved you 15 plus times a day. I assumed everyone’s parents fought their corner. I guessed everyone had broadly open minded, tolerant people in their lives who didn’t really care what you did as long as you were happy. And as I got older, I thought everyone sat around the dining table and debated politics and life and the meaning of things and laughed and told stories and invited other people to come and break bread and drink wine and join in.

They were not perfect – far from it. They argued like any couple and could be irrational like any human beings. Mum had a propensity to worry and boy could she hold a grudge. Although in truth those didn’t last much longer than the next social event, where she would meet the object of her irritation and soon they would all be laughing again.

She also suffered from perpetual imposter syndrome. She affected to be a sort of Home Counties Tory housewife, but it never really worked. At heart, she was always Hannah from Staffordshire. And thank God for that.

“I’m turning into that bloody Bucket woman,” she would say to me sometimes when awareness kicked in and start to laugh uproariously.

Such idiosnycracies made us love her more. And anyway, all of Hannah’s flaws were cancelled out by her inherent decency. She looked for the good in the world.

Later in life she ran a charity for refugees – and developed a deep regard for the people she helped and the stories they told. They loved her back – and their gratitude was palpable in the emails and piles of thank you notes she received. Her staunch and vocal defence of the rights of migrants and refugees was frequently at odds with the broadly Conservative people about her. Some old friendships didn’t survive the cut. She hated bullies and was never afraid to speak out when she thought it needed being said.

At a Conservative party function, in the early 2000s where Ann Widdecombe was speaking, my mother interrupted the then Tory MPs populist tirade against refugees and reminded her that she was talking about people.

“Are you a Communist?” Widdecombe fired back when she had finished. And my mother put her right on that as well.

Later life brought its trials. The loss of my father was raw and the 20 years of widowhood that followed were peppered with despair. But it didn’t stop her putting on the parties and when my children came along, she subjected them to the same torrent of jokes and stories and questions that my sister and I had had 30 plus years previously.

“I’m no good with babies,” she would say, but she was very good with children – because she didn’t treat them like idiots.

And then one day – about eight years ago – as I stood in the kitchen of our family home, wiping dishes and watching her through the window as my daughter brought her flowers – the curtain on her life’s story, slowly began to fall.

“Isn’t that a lovely scene!” My cousin declared, as she handed me a plate, “they both look almost child-like.” And I realised that something was wrong.

As Alzheimer’s took her from us, it was to be death by a million cuts. Well-meaning people would sometimes say to me:

“The old Hannah has gone” but this was still my mother. That glint in her eyes remained – long after words had faded away.

I have been so very lucky to have had this remarkable individual in my life – and luckier still to have had her as my mother, my staunchest ally, my stoutest defender, my harshest critic and my greatest inspiration.

“You’ll get there in the end,” she would say and strangely, even as she retreated from us – that began to happen. She never knew of all the things I wrote about her – or witnessed her beloved grandchildren grow into the remarkable young people they are.

But why dwell on what might have been? Hannah may have finally left the party – but how lucky we were that she came.

Lovely tribute Otto. I too remember decent Tories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Paddy

LikeLike

Lovely…

LikeLike

What a lovely tribute to a remarkable woman. Sincere condolences to you and your family.

LikeLike

Speaking up as someone influenced by your Mum Otto – all I want to add is my own gratitude, and to second your observations that Hannah was a life force! Where she got all that energy; where she cultivated all that genuine interest in other people; where she replenished that laugh; where she restocked her heart when it had been disappointed or hurt; where oh where is her source?I am looking still and marvel at the all of her robust and full tilt run at life. Amen dear Hannah – so glad to have walked a while in your company. Gemma

LikeLike

Xx love to you Gem

LikeLike

What a lovely tribute and what a wonderful woman your Mum must have been. X

LikeLike

Thank you for the hearty-felt tribute to your mum. You bring her alive in a way which brings together the personal & the universal.

A life well lived!

G Wood

LikeLike

This is beautiful and very moving, thank you for sharing it, your Mum sounds wonderful.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on litaenterprise and commented:

Beautiful tribute to a remarkable lady, shared by her son.

LikeLike

Absolutely beautiful tribute from a Son to a highly respected Mother

The Love; Admiration; Respect & Honor

Any Mother would be Proud

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing that loving, moving tribute to a fascinating human being.

LikeLike

What a wonderful tribute. Wow. I always love people who are multi faceted. My mother was similar in that she appeared Conservative but looked after minorities and broke taboos in WASP Claygate in the early 1960’s giving a home to the late saxophonist Peter King and his Afro American wife Joy Marshall

LikeLike